new_orleans_italian_lynching.jpg

new orleans massacre.jpg

negro records notice.jpg

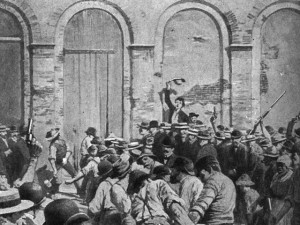

Cosimo Matassa was born in the US in 1926, a single generation after a vigilante mob stormed the parish prison to lynch and shoot eleven Italians prisoners to death. The mob violence was a message to the rising political power of the newly immigrated Italian community; “get back in line or else.”

The prison was located where the Municipal Auditorium stands today, just across Rampart Street where Cosimo would record New Orleans' musical history at his J&M Recording Studio. (Click here for map.) Cosimo's father, John Matassa, established the family's grocery store a couple blocks further from the massacre so he must have referred to this incident in teaching his son the immediacy and gravity of stirring New Orleans' racial sensitivities.

That was then. Today New Orleans has been branded as, “The Big Easy.” “The city that care forgot.” “The city of joie de vivre.” Nice marketing slogans but New Orleans parents still teach their children about the deadly undercurrents of race-based violence. No need to rehash examples, a mere two weeks ago we solemnly recalled how Hurricane Katrina washed away New Orleans' thin veneer of civilization and unleashed murderous violence from individuals, mobs and even traditional protectors such as doctors and police.

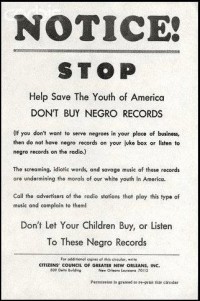

Cosimo Matassa's formal title is “sound recording engineer” but this narrow claim-to-fame skews and sanitizes the narrative of his life. Cosimo Matassa's profound significance was his bravery in challenging fundamental segregation rules by nurturing professional and personal relationships with musicians in whatever skin they wore into his studio. Professional respect? Cosimo didn't steal musician's intellectual property rights. Personal respect? Throughout his life Cosimo actively deflected praise mistakenly addressed to him right back onto the musicians. Privately Cosimo was just as decent. The record storage area of J&M Studios may have been the only place in New Orleans where these world-renowned musicians ever danced with a major demographic of their record buying public (white girls). And yes, until the mid-1970s when such adjectives went out of style, his name and his studio were distinquished not by today's praise but by a racial perjorative.

Cosimo knew the potentially grave consequences of his actions but he embodied the classic Italian culture of his and my father's "first generation" era,* that is; Cosimo studiously ignored the silly laws of his country and he actively shunned the pinch-faced segregationists' petty and mean-spirited rules. At its worst, my culture passed into criminality. At its best was Cosimo who ignored and shunned the segregationist barriers between whites and blacks and thereby released New Orleans music into popular culture. These releases tipped the delicately balanced social compact of segregation as millions of teenagers went screaming and dancing with joy from a rare tangible product of integration – a 45 rpm recorded at J&M Studios. By being a decent man in an extraordinary time, this self-taught recording engineer with a simple studio actually released a social contagion that abruptly challenged segregation. Make no mistake, behind Cosimo's self-effacing personality was incredible bravery. He stuck out his neck just across the street where vigilantes put ropes around the necks of his Italian ancestors to send a message of “no change wanted in New Orleans.”

Jamie Dell'Apa, WWOZ show host on

Saturday midnight to 3am (playing collectors music - often from the J&M Studios).

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Saturday-Night-New-Orleans-Radio/62577322...

* "The Urban Villagers" by Herbert Gans is the classic ethnography describing the Italian attitude towards their adopted country's social rules.

A video history of the role of Italians, Blacks and nativist New Orleanians that led up to the massacre:

My archived show with a summary of this posting at the end of hour one is available for streaming at:

http://www.prx.org/pieces/130345-140913-new-orleans-music-and-few-words-about-cosim